The 1940s - Postwar Crises

New Theatre History Home | Previous: The 1940s - Racism and Intolerance | Next: The 1940s - Workers and Industrial Action

The New supported the "Yes" vote in a referendum held on 19 August 1944 to give the federal government power to legislate on matters including the rehabilitation of servicemen, national health, unemployment, foreign investment, trust laws, monopolies and corporations and uniform railway gauges. The referendum was lost. Postwar social problems were the subject of a number of plays produced by the theatre.

In Ted Willis’ All Change Here, staged in 1945, overworked London bus conductresses, self-reliant during the blitz, have problems readjusting to their returning husbands:

Doll: Don’t you see? I’ve altered … you’ve altered … we can’t just pick it up where we dropped it in 1939. We’ve got to make a new go of it. If we don’t, Johnnie, so help me, it’s curtains.

Johnnie: Doll… mind what you’re saying.

Doll: I’m Doll Paine, see? What I do, I do in my own right. See? I’ve finished being a 1939 wife. I’m a 1944 woman … get it? We learned a lot in the last few years. The sooner you men get that … the better.

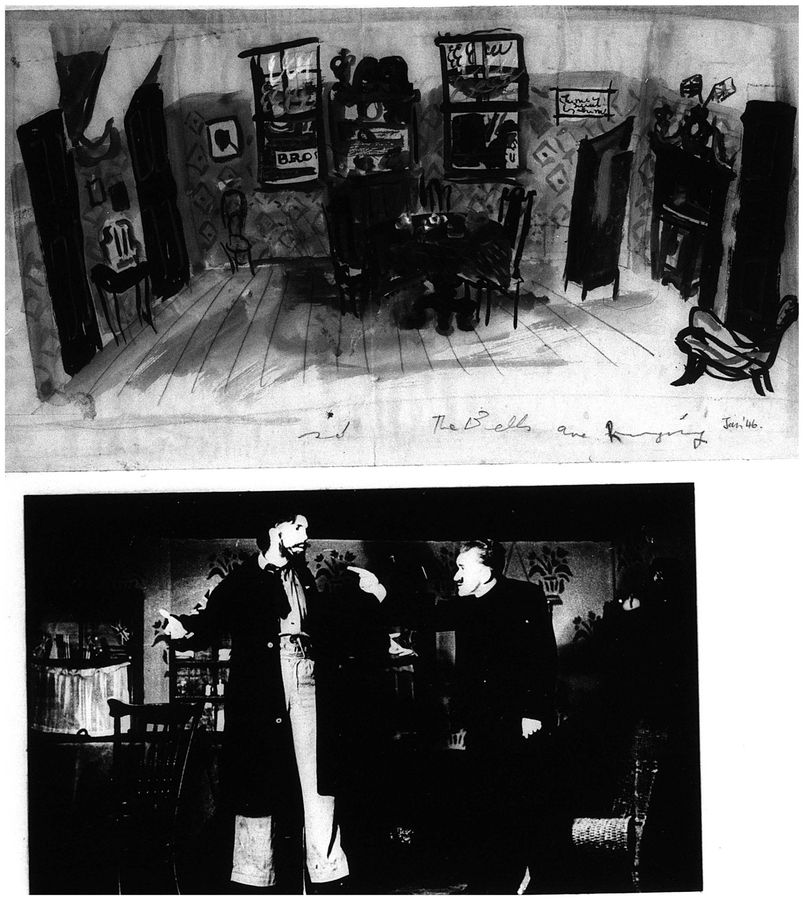

Set design was by Margaret Olley. Change bags and uniforms were borrowed from the NSW Transport Department, and the women were given tips on dress by bus conductress Lindsay Mountjoy. John Bates (aged 15) operated SFX, including sirens, planes overhead and radio "talk".

The Bells Are Ringing for victory in Willis’ play, staged in 1946, but not for the young who now have to deal with settling into peacetime employment:

Jenny suggests her son David could go back to his old job.

David: Bunson’s shop! Listen. I was 19 when I last worked there, just before I went into the RAF. They were paying me 40 bob a week as second counterhand.

Irene: But you will have to make up your mind soon. What else can you do?

David: Fly a plane. Fire a gun.

Jenny: Your father could fire a gun and fight when he came out of the last lot. It didn’t get him a job though.

David: I didn’t ask to become an object of argument. The Government made me dissatisfied with working in a shop. They’re the ones who’ll have to do something about it. There’ll be flying jobs around soon, when things settle.

The young also have trouble resuming relationships:

Min: Mum?

Jenny: Yes, girl?

Min: What would you say if I told you that John and me wouldn’t get married?

Jenny (quietly): I’d say it was your business. Yours and his. Like as not I’d ask you why.

Min: Aren’t the reasons obvious enough? We’re … well, we’re strangers, if you like. We’re not sure we’ll get on together – make a go of it.

Willis’ What Happens to Love? explored the same issues. Young couples, unable to find a home and forced to live in slums, are not prepared for family responsibilities and end up estranged.

The housing situation in postwar England, with little support from the public or private sector, was mirrored in Sydney where there was a critical shortage of accommodation for demobilised servicemen returning from overseas duty.

The setting of Jim Crawford‘s Welcome Home was an Australian bedsit:

A Digger’s hat is thrown on the stage followed by its owner in AIF uniform.

Mary: Billy…How did you get here? You’re not out of the army yet, are you … I posted a cake off to you only this morning … Billy!

Bill: It’s me all right… Got a lift down to Sydney in a Catalina, and a bomber as soon as we landed. Ninety days leave and my ticket, honey …

Mary: You’re not sick, are you dear? You’re looking thin and yellow.

Bill: M & V and Atabrine. I’ll be as handsome as ever when it wears off.

Atabrine was issued to troops in New Guinea after supplies of quinine were cut off by the Japanese advance. The anti-malarial drug was bitter, gave the skin a sickly hue, and produced side effects included headaches, nausea and vomiting.

Oriel Gray's My Life is My Affair explored the relationship between a returned soldier, his wife and "the other woman".

Flowers for the Living was staged in 1947 and 1949. Set in the “living” room of a London tenement after demobilisation, it argued for the eradication of slums. People should accrue benefits in life rather than death – flowers were for the living not funerals.

Home Brew, the first full-length play by NT member Joan Clarke, dealt with a working-class family who’d been through the Depression and Second World War and now had trouble finding housing. Based on her own experience living in one room with her husband and son, Clarke’s script was revised over a long period of time before its production in 1954.

Workshopped in 1948 was Stove, Sink and View Pat Bullen’s take on postwar real estate, its prologue:

There was an old owner who lived in a mansion

He had too many houses for further expansion

He divided them up for ulterior purpose

Then raised all the rentals and lived on the surplus.

A dull, dreary, characterless room, uninhabitable by humans, such as many people live in today.

Landlady: If you hang right out you get a lovely view.

Husband: Your advert said a cosy, modern flat,

Spacious and comfortable and moderate.

It’s not what we expected. I regret it

To think we rose at half past four to get it.

Landlady: There’s plenty more’ll take it, mark my words

They’re after rooms these days in droves and herds.

Enter plumber.

Plumber: Excuse me, m’am, I’ve come about the drainpipe.

Husband: You fool! There’s not a word to rhyme with drainpipe.

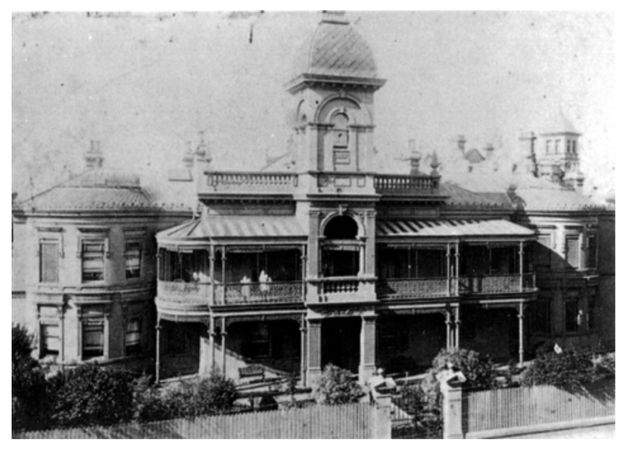

In real life NT members Evelyn Docker and Norma Disher lived in Maramanah, a 20-room Kings Cross mansion demolished in 1954 and its land incorporated in Fitzroy Gardens. For a time the theatre’s props were stored there. Evelyn was one of the building’s original 1946 “squatters”; in 1947 her brother ex-serviceman Bert Thomson was convicted as the ringleader of a group who trespassed Redleaf at Double Bay, the magistrate commenting that there were hundreds of other people in Sydney without accommodation.

New Theatre History Home | Previous: The 1940s - Racism and Intolerance | Next: The 1940s - Workers and Industrial Action